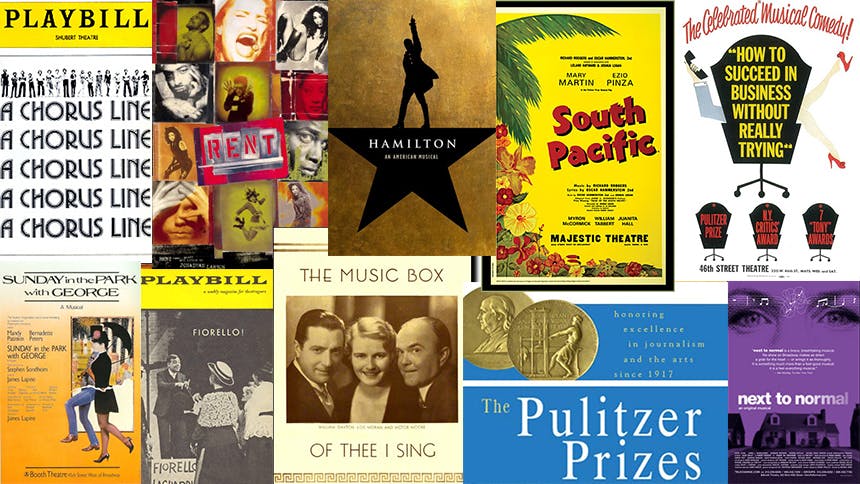

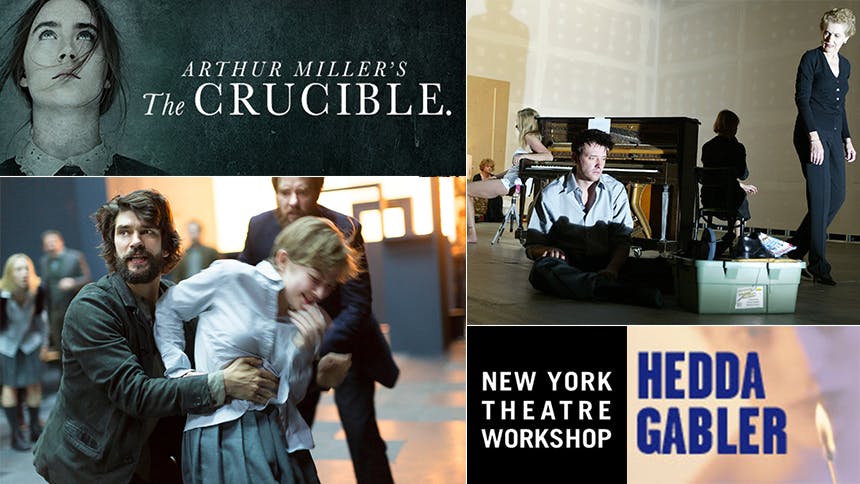

Drama Desk-nominated stage and screen star Jason Butler Harner returns to Broadway this spring as the fire and brimstone preaching Reverend Parris in Ivo van Hove's critically-acclaimed revival of Arthur Miller's The Crucible., marking a reunion for the actor and director who previously worked together in NYTW's Hedda Gabler in 2004.

Photo by Jan Versweyveld

BroadwayBox caught up with intelligent, thoughtful actor to find out how he went about creating his Reverend Parris and what the three biggest inspirations at play were when tackling this incendiary and tortured character.

I am very aware of doing this play today—yes of course with the political world and the impact of religion, but for me personally what I have to inhabit with Parris. Miller has written that he’s a widower, and I was interested in him raising a child, not only his own daughter but his niece that has shut down and he can’t access her. She’s cold and apathetic. I didn’t know before coming into the production how much Ivo was going to investigate that aspect of their relationship.

I had known for a while that I was going to be in Salem for the spring, and I was very excited (and of course very grateful) to be there with Ivo and these actors, but I had a hard time finding the in to the world. And having worked with Ivo before I knew that specific forms of research would be up to me and less of particular interest in the rehearsal room. So I was looking for something to start the fire and it comes it in the weird places.

I happened to be in Madrid in the fall by myself and I went to the Prado Museum where I saw a number of paintings that day which opened the door. The first one was this painting by Francisco Goya called Vuelo de Brujas, and that sort of triggered something. Coincidently at the museum at that time, they were showing The Black Paintings series of Goya, and I felt something percolating when I was there and got really excited.

Then I happened to run a few blocks down to the Reina Sofia, the modern museum in Madrid, and there was this exhibit by Hito Steyerl called “Is The Museum a Battlefield”. In that, she did this thing where she traced a bullet that killed a friend from a battlefield in Turkey to the manufacturers then was able to ultimately connect that the warfare manufacturers were also the people funding the museums, and she gets grants from these museums; so basically she’s saying what’s my level of culpability and responsibility? The combination of that day (being in another city, in another experience, seeing the paintings then this installation) was the thing that opened up the play for me and I started to feel things. Then bizarrely, the next day the Paris attacks happened so it all became one moment in terms of the first chapter in this experience of The Crucible for me.

Then phase two was the research step, which I really, really love. When I got home I was finally motivated to crack open that Stacy Schiff book The Witches—which had been sitting on my bedstand since the beginning of August, but it was so daunting—and boy was it terrific. She used the same source material that Miller did for the play, which is Marion Starkey’s The Devil in Massachusetts. Schiff was able to articulate basically what it’s like to live in this time period. It’s so dark at night; you are this far apart and this desperate; the people are arguably suffering from PTSD before Salem happens because of what it took to get to America and survive in this land; then, of course, how these girls are treated and what is happened.

There are two essays that Miller wrote that I am constantly looking at, even now in our seventh week of production. He wrote an essay for The New Yorker called “Why I Wrote The Crucible”, and he had also done this speech in May of 1999 on The Crucible which Tavi [Gevinson] gave me in the first week of rehearsal. Those two essays are a godsend for me. I walked into the play with a certain amount of history and subjectivity about the play, and with those essays of Miller’s I was able to see more. There were incredible things he talks about: fear and how we are all culpable. He makes a correlation between fear and love and how fear doesn’t travel well. With fear and love, as you get further away from them you forget their actual fullness of feeling until it happens again. It answered some of the questions I had had walking in the door.

At some point in the creative process little gifts keep popping up that are echoing the play and leading you to the fullness of what the play and character are asking you to do—and that’s where the really good fruit lies. The last component I had to look at was the Diane Sawyer interview with Sue Klebold, the Columbine shooter’s mother. I was fascinated by her. It really touched me in a way—not only because how she articulated the shame and pain she feels and how it has changed her life, but also to some degree this expectation that I had of her to explain things she can’t possibly explain. Within the interview she said she was trying to be respectful of her son’s teenage years and not be up in his business and how much she regrets that. There’s also something about her, which is that not all people are meant to be leaders of men and women. When catastrophe happens one’s ineffectualness could suddenly be perceived as catastrophic, but people are people doing the best they can. As much as Reverend Parris is a coward ultimately and culpable for incredible damage and pain and death, there is another part of him just trying to survive the best he can. The nature of his ego coming into play and his concern for his daughter, first and foremost, really brings down the demise of this whole community.

See Jason Butler Harner's Reverend Parris live in Arthur Miller's The Crucible. at Broadway's Walter Kerr Theatre through July 17.