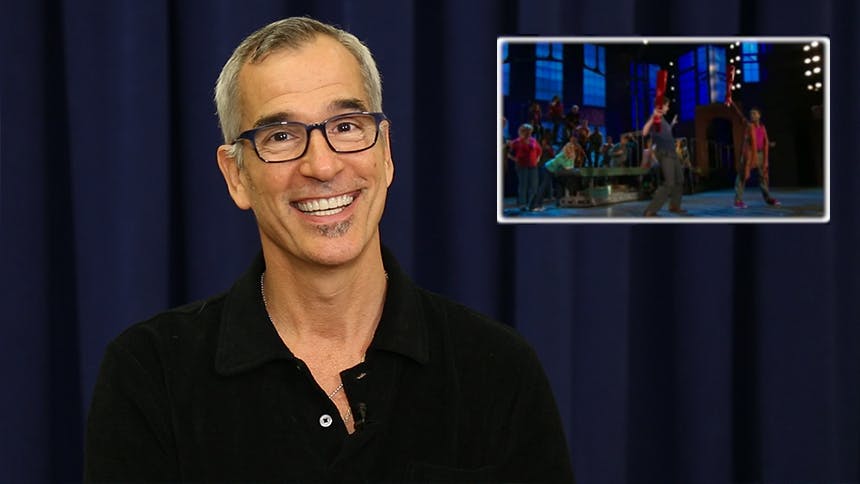

Scenic designer Dane Laffrey received his first Tony nomination this year for his incredible, immersive reimagining of Once On This Island

. BroadwayBox caught up with Dane to learn about transforming Circle in the Square Theatre, hidden secrets of the set, and the real-life & mythical inspirations behind what you see.

Creating an Experience Inside the Theatre

Being given Circle in the Square for this show was the greatest possible gift. It's the only Broadway theater like it, and it really allows you to make something immersive and experiential. I wanted it to feel like the design and the theater were becoming one and the same. The idea that the disaster of a hurricane has befallen the island and the world of the story and also Circle and the Square itself.

According to Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty, Once On This Island has been done literally tens of thousands of times since its Broadway premiere. It often has a fairy tale or folkloric aesthetic, and we definitely felt a need to cut against that in this wholesale reimagining and reinvention of this revival. A big part of that was about wanting to make an experience, and our theatre allowed us to do that in an exciting way—it only has three doors, and when you come in, you're at the top of an arena.

The glimpse through every door was considered as we installed the space. The experience really begins for you from the moment you walk in. Hopefully by the time you've reached your seat you already feel transported and ready to receive a new experience, which I think is a great way to watch theater.

It was really a long form labor of love to install that space and detail it out and give it as much dimension and detail as we possibly could so that every audience member felt that they were having a completely full 360-degree experience but also that they were having a unique experience based on where they're sitting and what they can see.

A Community Rebuilding

The trip to Haiti changed a lot of things a lot about the design. One thing that I can specifically talk about is that we introduced the idea of a few more layers of damage and wreckage in the space, and then a concerted effort to show that reconstruction was in process.

We've added a number of walls on stage that look like they're the walls of Circle and the Square, but they're not. They come in (mostly on stage right) behind our added bank seats to help shape that space a little bit. We have one whole wall that's fresh cinder blocks in the process of being rebuilt, held up by a kind of makeshift scaffolding. Another place the wall is broken and a tree is growing through it.

The idea about that was really to capture the sense that this place, and the people making up our community of storytellers are not mired and wallowing. They are vibrant and alive, and they're constantly rebuilding. I think that was a huge takeaway. It was so easy for the initial research—things like natural disasters of the scale of the 2011 earthquake in Haiti or Hurricane Matthew—to be all about this totally epic destruction. The story those images don't tell is how you immediately start to rebuild from that. That's the story that we wanted to tell. I think that's the story of Once On This Island—in spite of everything we rebuild. We pass on our stories. That was a huge takeaway.

Finding the Musical’s Fundamental Tree

It was a long process. What it ends up being is the resurrection of this downed power pole. The power pole was an element of the design from really early on—the idea that this big heavy thing had fallen and crushed a bunch of seats underneath it and was just lying there in the middle of the audience felt like a great, exciting, immersive, muscular gesture. But then we didn't know what we were going to for the tree and it's such a hugely important moment but a tricky transformational moment that can't be handled in a literal way.

I think with most design processes, but certainly with Once On This Island, you have to follow the research. We dug back in and we spent a lot of time researching Afro-Haitian vodou practice, which is the spiritual source material for the gods in Once On This Island. In every vodou temple, there's a central pole, and it's not really a structural thing, but rather a spiritual emblem that represents the connection between man and the gods, or the earth and the sky. They're beautifully and vibrantly decorated. Then we discovered that a tree can be used in the same way outside the walls of a temple. That felt like a bit of an "Aha!" moment

The final piece of that puzzle was a decision to allow our company the opportunity to share images and mementos that were meaningful to them associated with people that they've loved and lost. That, in combination with some Afro-Haitian vodou imagery, is what encrusts that pole and what makes it such an enigmatic thing. If you look closely at it, it's a lot of family photos (grandparent, parents, friends & pets). It's our connection between mortals and gods: the path that Ti Moune takes to move between worlds. It's also a connection between our company (our actors who are storytellers) and the characters they play. It's a beautiful spine that connects all of us.

Constructing Agwe’s Flood

We knew we wanted a strong element of water present constantly, and I wanted it to feel like the theater was flooding from the basement and being held with sandbags. Basically, we just actually flooded out the architectural vom in the theater, which sort of steps down from stage level and becomes knee-deep at the back. Otherwise, it's pond liner that's shaped and wrapped inside that architecture with corrugated metal and plywood and old signs.

The thing that's complicated about it is the heating and filtration. Equity says that it has to be heated to a certain temperature, so we do that, and we also filter the water and completely change it out it every couple of weeks and the interior of the pool is scrubbed. It took some work in tech and with the actors to figure out what was ideal, but the bottom of the pool is a combination of rubber bar mats covered in a layer of black rubber mulch—just ground up tires. That provides grip for the actors so they don't slip and also gives a mysterious, organic look to it. That was a little bit of give and take, we were really glad to learn that rubber tires don't float when they're ground up. Most seats just see the reflection on the surface of the water but if you're sitting right above it you can see in.

Shaping the Sand

I think the initial quantity was somewhere between five and six tons. It completely covers the playing space and back into the wings, and it's between three and five inches deep depending on where you are. It's a little bit temperamental but also rather wonderful.

One secret about the space and the sand is that there' s no drainage in the floor for anything. In the show, it rains really hard for 30 seconds or so during “Rain”, and the sand just absorbs that water. The water doesn't go anywhere, which is amazing because we would not have been able to have a sand floor and rain if we needed drainage. When it's damp, it gets compacted and is a much better surface for the choreography and better for the actors. The look is also a little better. It looks like it's just rained. I was always concerned that it look like an idyllic beach. It needed to feel like a little wetter and a little more desolate than that.

The reveal of the rug is really, really simple. There's just basically a pair of tarps with handles that live under the sand that no one can see—nor have I actually ever seen, and I really know what I'm looking for! I have literally never seen those handles. I know where they are, I know what they look like, and I never see them—which is pretty cool.

This rectangle of sand represents a big shift in the storytelling vocabulary. The costumes take a big leap at that moment, too.When the story turns past the number “Some Say” into the section where Ti Moune is in the city, she's gone beyond the world of the community of storytellers, and it becomes a little more conjectural. We took that as license to morph our vocabulary a little bit into something that was a bit more fantastical, where you could peel back sand and discover a giant oriental rug and clothes that look like the ghosts of a colonial past appearing.

The Addition of the Truck

That’s a real truck. It was an early piece of research. It's one of those things that you can sometimes see after a horrendous category five hurricane. You'll find a photo of semi-trailer truck up a tree, literally. That was an image that I had in the studio for a long time. I felt it was a powerful way to capture the kind of cataclysm that exists at the beginning of this story that it would be a touchstone for us.

As we were beginning conversations about fabricating it, it became really important to me that it had to be the real thing. I just felt that it needed to have had a life and have that weight and that rust and that age and the sound that the door makes, which we end up making pretty significant use of in the show. It was found in Canada, brought it in, completely disassembled it, split it into sections small enough that it would fit in a freight elevator, and reinforced it heavily so that the band can sit on top.

Then the shop concocted a brilliant system whereby it was put back together sitting on its axle and wheels in a way that you would never know it had been meddled with. It's a remarkable, mad piece of construction. The paint finish is something that came from a piece of research of a truck in Haiti. Because it's cutoff and hidden, no one knows what it says, but the truck says "Wait For God".

See Dane Laffrey's Once On This Island set IRL at Broadway's Circle in the Square Theatre.