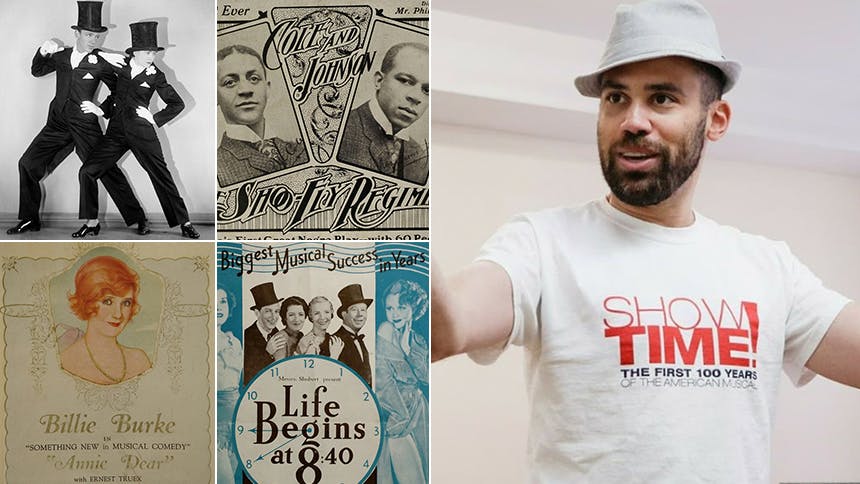

Theatre historian and founder of UnsungMusicalsCo., Ben West brings something totally new to the art form with Show Time! The First 100 Years of the American Musical, a live-action documentary musical created, written, and performed by Ben (and featuring over two dozen songs!) that charts the seven eras of the American musical from the mid-1800s through 1999. The first in a trilogy of Show Time! pieces, The First 100 Years runs September 13 through 16 at off-Broadway's Theatre at Saint Peter’s.

In anticipation of the show every major theatre nerd should see, Ben shares with us five tidbits most musical fans might not know about that first 100 years in NYC.

1. The Brilliance of Hassard Short

Are you too a fan of the deft double turntables employed by designers David Korins (Hamilton) and David Rockwell (Dirty Rotten Scoundrels)? It is visionary director and lighting designer Hassard Short who is largely credited with popularizing the sly scenic effect with his staging of The Band Wagon (1931). In a career that revolutionized theatrical stagecraft and musical storytelling, Short utilized moving scenic platforms for Irving Berlin’s Music Box Revue (1921), removed the customary footlights and added instead a row of lights along the front of the balcony for Dietz and Schwartz’s Three’s a Crowd (1930), and gave sweeping grandeur to the dual-worlds of Moss Hart’s Lady in the Dark (1941). His other landmark entries include As Thousands Cheer (1933), Carmen Jones (1943), and the 1946 revival of Show Boat, for which he was handpicked by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, who explained, “Ziegfeld’s opulent original production was just as essential as our words and music, and any new production must supply an equivalent to his contribution. This is a big order. That is why Jerry and I called in Hassard Short, whose taste and knowledge of costumes, scenery, and lighting are unequaled in the modern theatre.”

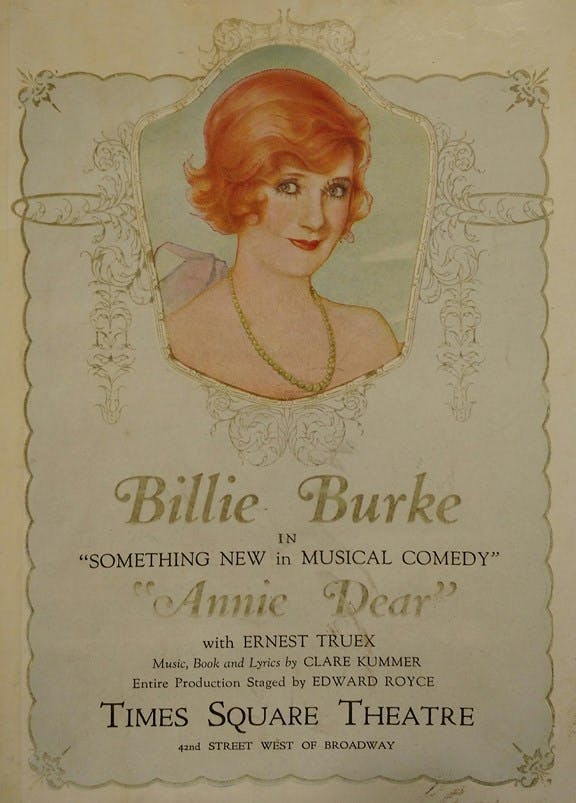

2. Early Female Writers Flourished

Dorothy Fields hit the scene in December 1927, writing her first Cotton Club revue with composer Jimmy McHugh. By 1928, she was on Broadway with Blackbirds of 1928 and Hello, Daddy. Over the next fifteen years, Ms. Fields’ would be the most prominent female voice in the American musical, which also saw infrequent contributions from the likes of Nancy Hamilton, Muriel Pollock, and Ann Ronell. Following World War II, Betty Comden, Carolyn Leigh, and others joined Ms. Fields in writing steadily for the theatre. But often overlooked are the many female scribes who shaped the form during its infancy, pre-Dorothy Fields: Rida Johnson Young (Maytime), Clare Kummer (Annie Dear), Alma Sanders (Tangerine), Dorothy Donnelly (The Student Prince), and Anne Caldwell (The Fred Stone Musicals) being only a handful of them.

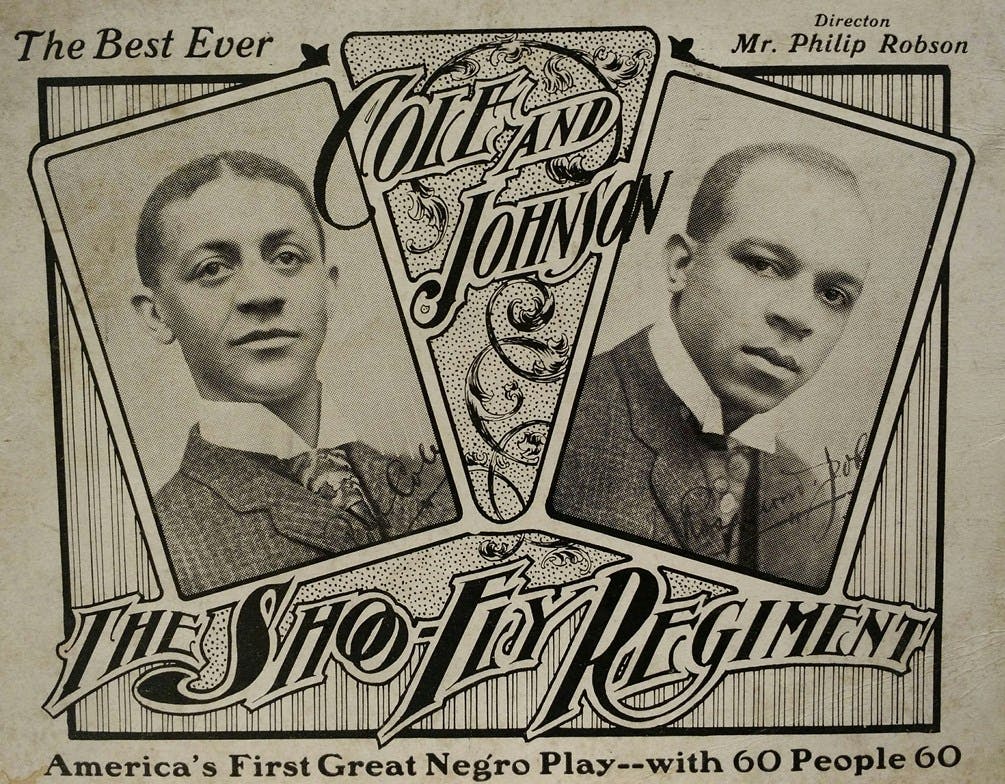

3. The Black Writers Boom

There is a common misperception that the seminal 1921 sensation Shuffle Along was the first all-black musical. It was not. Recently, writer-director George C. Wolfe and producer Scott Rudin further argued in their incomplete history of the historic work that its creators were the first black writers to succeed on Broadway. They were not. Though this does not and should not diminish the seismic shift that Shuffle Along delivered, it is important to note that, despite segregation, racism, and rampant inequality, the first decade of the 20th century was an extraordinary time for black-authored musicals. Jesse A. Shipp, Will Marion Cook, Alex Rogers, Rosamond Johnson, and Bob Cole are just a few of the many African American artists who were actively writing for the musical stage. Cole was, in fact, the creative mastermind behind the first legitimate all-black musical comedy, A Trip to Coontown (1897-1901). In reviewing the first of its seven New York City engagements, the New York Sun called the musical, “A great big whacking success.”

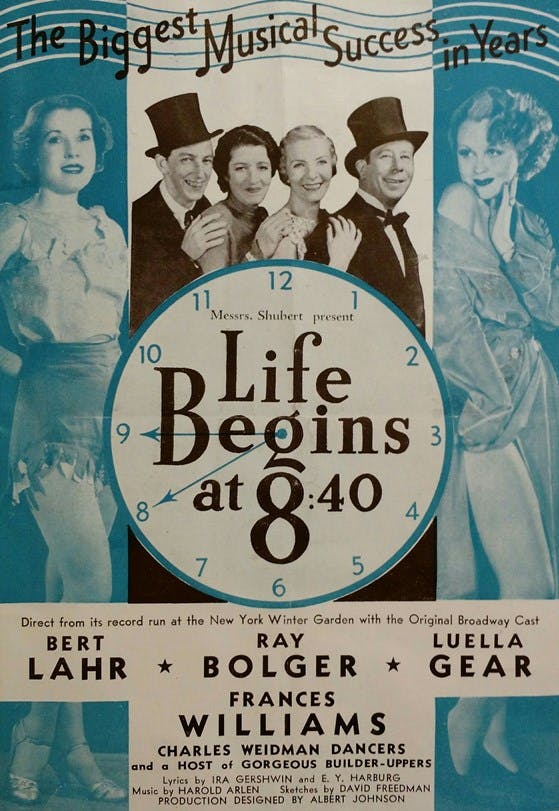

4. The Revue Revolution

In 1894, Life Magazine described the Revue as “a new development in the form of variety show entertainment.” By 1950, the iconic theatrical form would virtually disappear. But during the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, the Revue would prove to be one of the most instrumental forces in the development of the American musical. Not only did it directly influence the style, structure, stagecraft, skill, and storytelling of the book musical, the Revue was an artistic incubator for an incredible number of writers who defined the American musical’s Golden Age, including Frank Loesser, Richard Rodgers, and E.Y. Harburg, who explained: “Writing for revues was the only way really that young writers could get started in the theatre, but it was a wonderful way. Revues were constantly being written. And most of the revues were contributions by people—by youngster—who had come around with songs. So, an up and coming writer really had an opportunity to show his wares and get a song placed in a show here and a show there, stand behind the back of the audience, and see what the song was evoking from an audience; and by that terrific practical experience, could tell what was wrong with the song, how it affected an audience, what to do next time.”

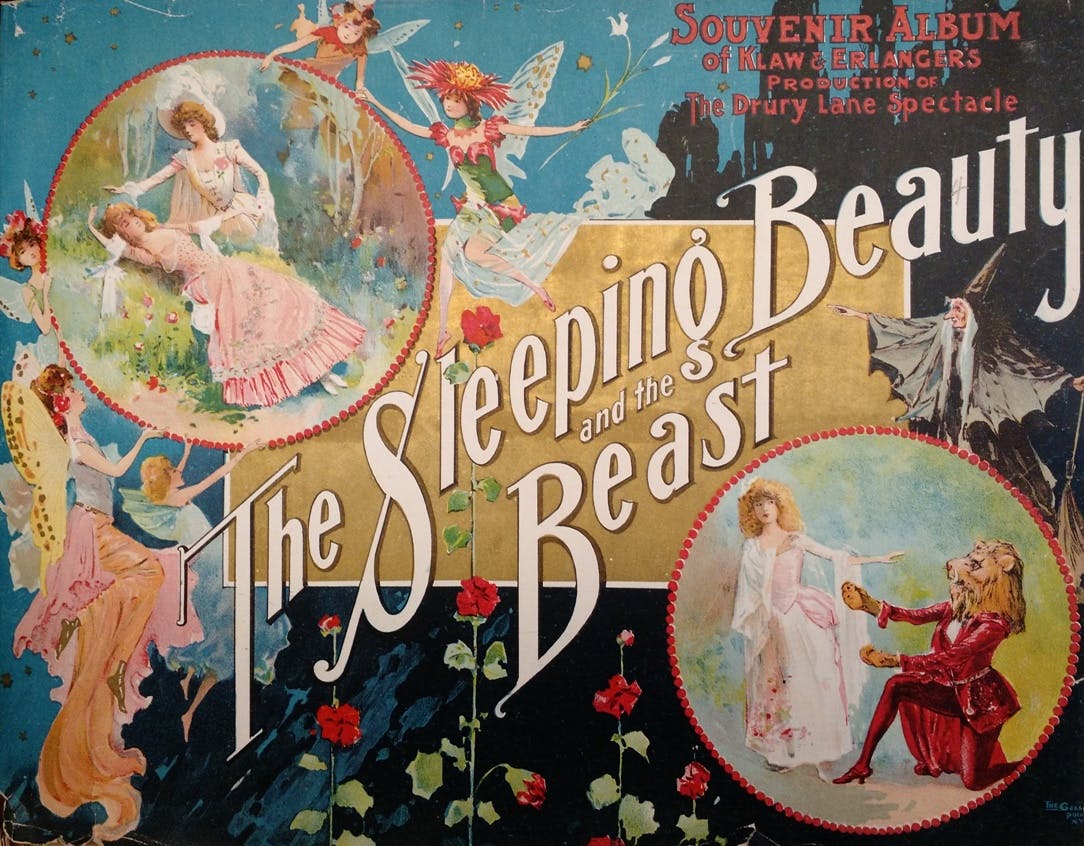

5. U.K. Mega Musicals Are Old News

Originating in the United Kingdom, Cats, The Phantom of the Opera, Miss Saigon, and several other so-called Mega Musicals transfixed the New York stage in the 1980s and ‘90s. But they are hardly the first of their breed. Producers Klaw and Erlanger, for example, imported several London extravaganzas in the early-1900s. Of their impending 1901 offering, The New York Times reported, “The Sleeping Beauty and the Beast is one of the largest productions ever made at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and will be staged here with all the original scenery, including the famous Crystal Palace scene. The mounting of the production at the Broadway Theatre will require extensive alterations in the stage. These will be made during the summer recess. More than 300 people will be employed in this presentation.”

Check out Ben West in "Show Time! The First 100 Years of the American Musical" at off-Broadway's Theatre at Saint Peter’s September 13-16.